Thou art that

Success is an embarrassing word to use in the context of your own life. But worse is lying/denying success for the sake of humility and thereby creating artifice. In this sense, I have to say that my studies in Australia were a success. I had published good papers, worked hard and survived some difficult moments over many years. It was the success that help me land a ‘good’ job in London and to be able to make my dream move with a certain sense of confidence and optimisim. In the end, it didn’t last long.

I worked hard, but I couldn’t get interesting results. The project had limited direction and all the life seemed to be draining away from my ambition. With this my confidence dropped and the hope of more success plummeted. I worked in a lab where my project seemed far away from the rest of the group. I was isolated up front, as it were. In the end, less than one year later, I asked my boss if I could leave.

The next year was better and equally horrible at the same time. It took a lot longer than I hoped to leave to get to Spain where my heart was. The first year here in Iberia was also a difficult process, but after a difficult time, the road seems to have direction again.

The point is not to exaggerate myself, but to make a comparison.

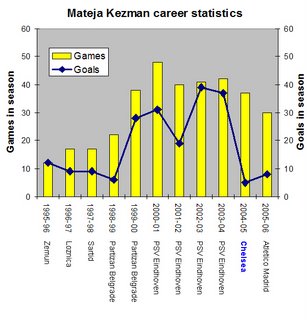

Mateja Kezman, was born in Belgrade in 1979. He started his career in Zemun in the 1995-96 season before making the switch through Loznica, Sartid to eventually sign for Partizan Belgrade in 1998. After two years he moved again to PSV Eindhoven at the age of 20. In four years at the club, and before, he netted an incredible number of goals (see figure). It can only be said that Mateja Kezman was successful and on the brink of more.

In 2004 he was bought by Chelsea and made the dream move to the west London club along with PSV teamate Arjen Robben. Kezman only lasted one season, netting

a paltry 5 goals in the league and cup competitions (see figure). Yet one can’t forget his performance in the second leg against Barcelona, bursting forward and wide to set up the first goal. Again, he scored the late winner against perennial enemies Liverpool in the League Cup final. The first time I saw him live in the flesh, he all but knocked Scunthorpe United out of the FA Cup with one of Chelsea’s three goals, the soon-to-be champions having been forced to chase the game after 7 minutes. But that was all.

a paltry 5 goals in the league and cup competitions (see figure). Yet one can’t forget his performance in the second leg against Barcelona, bursting forward and wide to set up the first goal. Again, he scored the late winner against perennial enemies Liverpool in the League Cup final. The first time I saw him live in the flesh, he all but knocked Scunthorpe United out of the FA Cup with one of Chelsea’s three goals, the soon-to-be champions having been forced to chase the game after 7 minutes. But that was all.I only recently saw some of Kezman’s goals at PSV

and it seemed miraculous to me that he could have scored so many. Almost all of his goals, including the one at Scunthorpe, were poachers goals, stabbed in from close range. Even his first Chelsea goal was a late penalty in a game that Chelsea were already winning by two or three. Mourinho had gestured from the bench to insist that Kezman take it, knowing that a goal would lift his confidence. It didn’t really in the end. After one year, Kezman too had made the shift to Spain, signing for Atletico Madrid. Only the English press seemed to know what went wrong.

Our lives thus share a homology, though certainly Kezman has scored many more times than I have. Our lives follow the basic path of Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, tracing it through ‘The Call of Adventure’, ‘The Belly of the Whale’, to ‘The Road of Trials’. Whether we have yet made it to the stage of ‘Ultimate Boon’ or ‘Freedom to Live’ remains to be seen. Regardless and thus far, through this mutuality, there is a certain fraternity and protectiveness over our real and dreamed experiences. There is an empathy. Kezman for me is a symbol, an archetype. Kezman is the living myth, the “public dream”.

However, to fully use Kezman to understand life more deeply, one has to accept the writing of Campbell and the idea that myth is able to serve as mentor, as measure or even as a map of the labyrinth that we muddle through. Or in Campbell’s own words, “That which is beyond even the concept of reality, that which transcends all thought. The myth puts you there all the time, gives you a line to connect with that mystery which you are.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home